Unexpected Lessons from breaking Webgames

One of the reasons I started programming was to code exploits in webgames. The other reason involves a certain 1980s text adventure, but that is a story for another day.

|

|---|

| Almost as sarcastic as Zork, but in first person |

Looking back, I realize that this unconventional way of getting into programming exposed me to several important concepts early. Let’s look at a few from the perspective of a programming noob. All code can be found as gists.

Protobowl.com

I played NAQT Quiz Bowl in high school. When I found out about protobowl, an online real time multiplayer quizbowl webapp, I immediately sunk hours into it. Occasionally finding players buzzing in suspiciously early, I decided to probe for exploits.

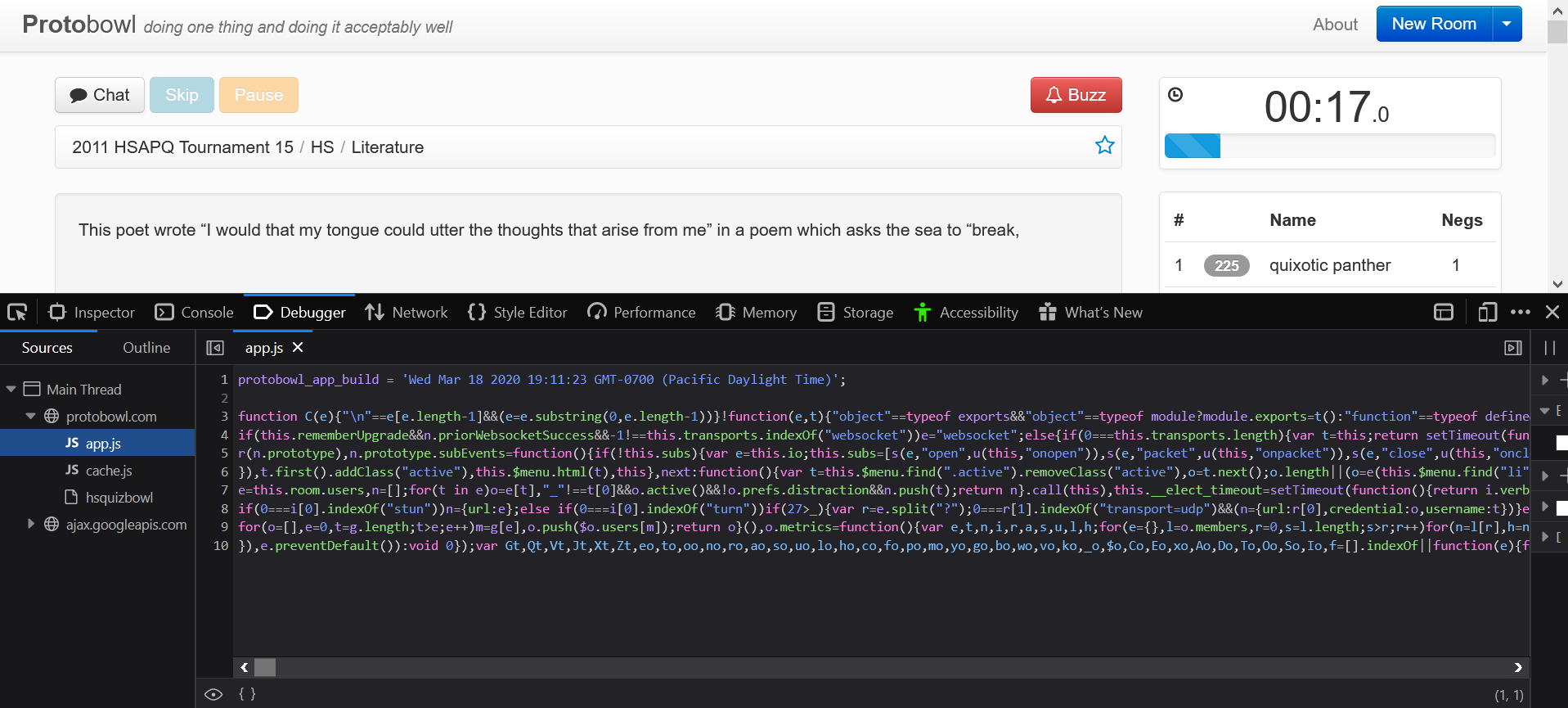

This was my first exploit, so the only tool at my disposal was the trusty F12, CTRL-SHIFT-I, or right-clicking ‘Inspect Element’ to pull up the in-browser developer tools. I quickly realized that the file called app.js I was looking at in the debugger wasn’t source code.

|

|---|

| Definitely not source code |

Code Obfuscation

Obfuscation is the process of deliberately making code hard to read by humans. In the case of a JavaScript app like Protobowl, it makes the scripts sent to the user for the web-page smaller and quicker to download. This meant that while they will be harder to find, if there is a vulnerability in app.js, I would be able to execute it on my device (the client).

A common pattern in obfuscation is renaming variables from their human-readable names to typically 1-2 letter names. However, you cannot change strings without changing the behavior of the program. Therefore, any string found in the source code will be found verbatim in the obfuscated code I find on my device. The tricky part would be finding a string that would lead me directly to a vulnerability…

CSS Selector Strings

My idea for a vulnerability was to trigger an event to reveal the current question’s answer before the question had actually ended. I knew the HTML for the page looked like this:

<div id="history">

<div class="bundle qid-54769933ea23cca9055100a1 active">...</div>

<div class="bundle qid-5476da99ea23cca905518219 revealed">

<ul class="breadcrumb">

<ul>

...

<li class="pull-right answer done">

The Answer!

</li>

</ul>

</ul>

...

</div>

</div>

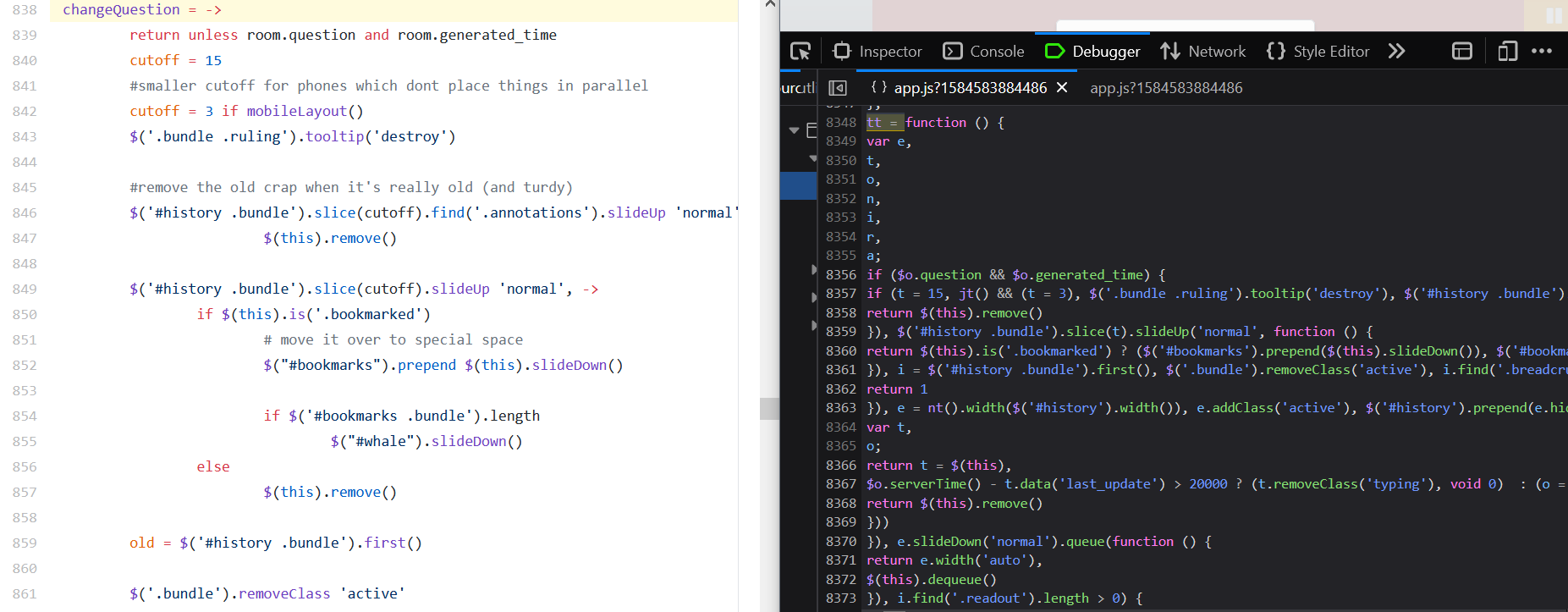

Of course, the first things I searched in the obfuscated code were ‘bundle’, ‘history’, ‘breadcrumb’, and ‘pull-right answer.’ Sure enough, I’d find a function called tt which turned about to be this function after obfuscation. It was exactly what I needed.

|

|---|

| Can you see the resemblance? |

To avoid ruining the puzzle, I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to grok each line of the obfuscated code.

I’d later learn to look for the window object in the console several w3schools pages later. I was surprised to find out that all global functions and objects are children of this window, including one called $o (at least it was called that in the build at the time) that contained the answer to the current question.

Automation

Turning this exploit into a point farm would yield what I consider to be my first lines of code.

setInterval(function(){

tt();

$(".buzzbtn").click();

$(".guess_input").val($("[class='pull-right answer done']").first().text());

$(".guess_form").submit();

$(".nextbtn").click();

}, 7000);

The version I made after discovering window:

setInterval(function(){

$(".buzzbtn").click();

var guess = $o.answer;

// only the essential part of the answer is surrounded by '{}'

$(".guess_input").val(guess.slice(guess.indexOf('{')+1, guess.indexOf('}')+1));

$(".guess_form").submit();

$(".nextbtn").click();

}, 7000);

|

|---|

| Of course, the first thing I tried was changing the interval to 1 second |

The first code I ever read was obfuscated, and the first code I ever wrote was a webgame exploit. It’s an unusual first exposure to code, but I’d argue that this natural introduction to the DOM, HTML, and CSS gave me a good start as a beginner.

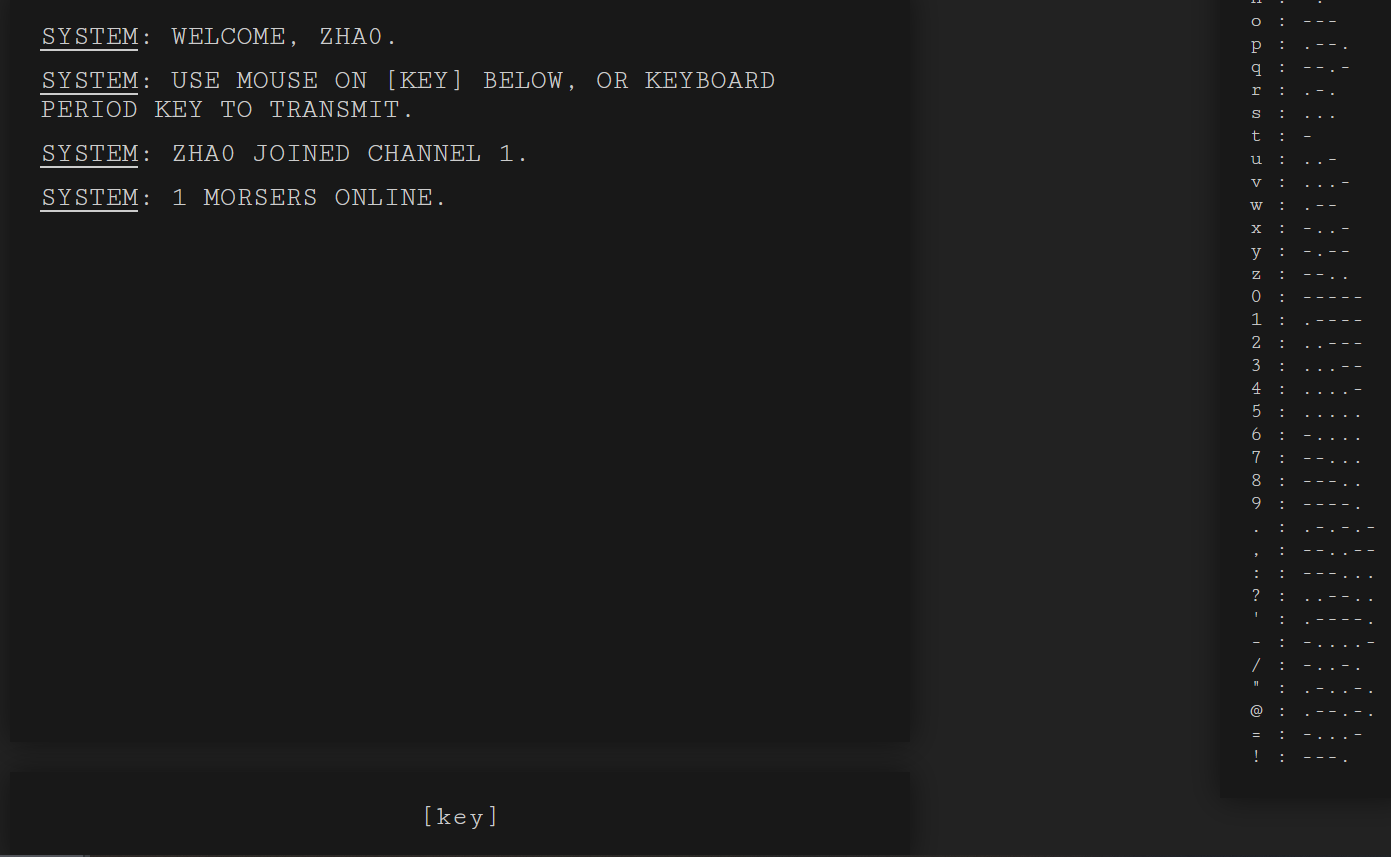

morsecode.me

This is a weekend project by Burak Kanber that hosts Morse code chat rooms. In my attempt to create a tool to allow me to chat without knowing any Morse code, I got a healthy taste of JavaScript higher-order functions, concurrency, and Promises.

|

|---|

| I didn’t know you were skilled with broadswords, Prince Zuko |

The idea

Instead of using the button to emit the ‘dits’ and ‘dahs’ of Morse code, let’s create a tool that will translate your keypresses into the appropriate dits and dahs.

Signal duration

We can use mouseup and mousedown events to trigger the signal, but there needs to be a way to sleep between those two events. There isn’t any sleep function, but asynchronous functions can pause their execution until another function returns a fulfilled Promise. Here, a Promise is an object that holds information on the completion of an asynchronous call. It is said to be fulfilled when that call is completed.

If our asynchronous call is setTimeout, we can create our own ‘sleep’ from scratch.

function sleep(ms) {

return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, ms));

}

Thus we have

async function dit() {

$(button).trigger("mousedown");

await sleep(100);

$(button).trigger("mouseup");

}

async function dah() {

$(button).trigger("mousedown");

await sleep(300);

$(button).trigger("mouseup");

}

to emit our dits and dahs.

Dispatch system

Initially, I wanted to add letters to a queue whenever the user pressed a key. The queue would be addressed by a setInterval that periodically called dit and dah. However, this doesn’t work. setInterval works by calling the same callback function over and over in an interval, but asynchronous functions (like one that would call dit and dah) can only resolve a Promise once.

To get around this problem, I decided to use the fluent interface design pattern. Essentially, it uses method chaining to provide an efficient interface. You might have seen it while reading jQuery code or even in the Protobowl obfuscated code like with this line:

n.append($('<ul>').addClass('breadcrumb').append(o)).append(s).append($('<div>').addClass('sticky')).append($('<div>').addClass('annotations'))

It’s not hard to make a fluent interface in JavaScript. Just have each method return this in order to preserve the context for the next method. I’ll leverage this fact, along with the fact that Promises can chain callbacks using .then(), to create my own fluent interface for dispatching the dits and dahs.

async function dit() {

$(button).trigger("mousedown");

await sleep(100);

$(button).trigger("mouseup");

return this; // + this line

}

async function dah() {

$(button).trigger("mousedown");

await sleep(300);

$(button).trigger("mouseup");

return this; // + this line

}

document.addEventListener("keypress", async function(e){

// get the corresponding dashes and dots for the key that was pressed

var ditdah = table[e.key];

[...ditdah].reduce((composing, curr) => curr === '.' ? composing.then(dit) : composing.then(dah), sleep(100));

});

The glorious one-liner

The solution combined using the spread operator to expand the string made up of dashes and dots into an array of characters,

// var ditdah = '-.';

[...ditdah]

// ['-', '.']

using the reduce higher-order function to build the chain of Promise callbacks,

.reduce((composing, curr) => curr === '.' ? composing.then(dit) : composing.then(dah), sleep(100));

| iteration | composing | current | return |

|---|---|---|---|

| start | ['-', '.'] |

||

| first | sleep(100) |

'-' |

sleep(100).then(dah) |

| second | sleep(100).then(dah) |

'.' |

sleep(100).then(dah).then(dit) |

and even a ternary conditional to make the whole line super idiomatic.

|

|---|

| I still don’t fully know Morse code |

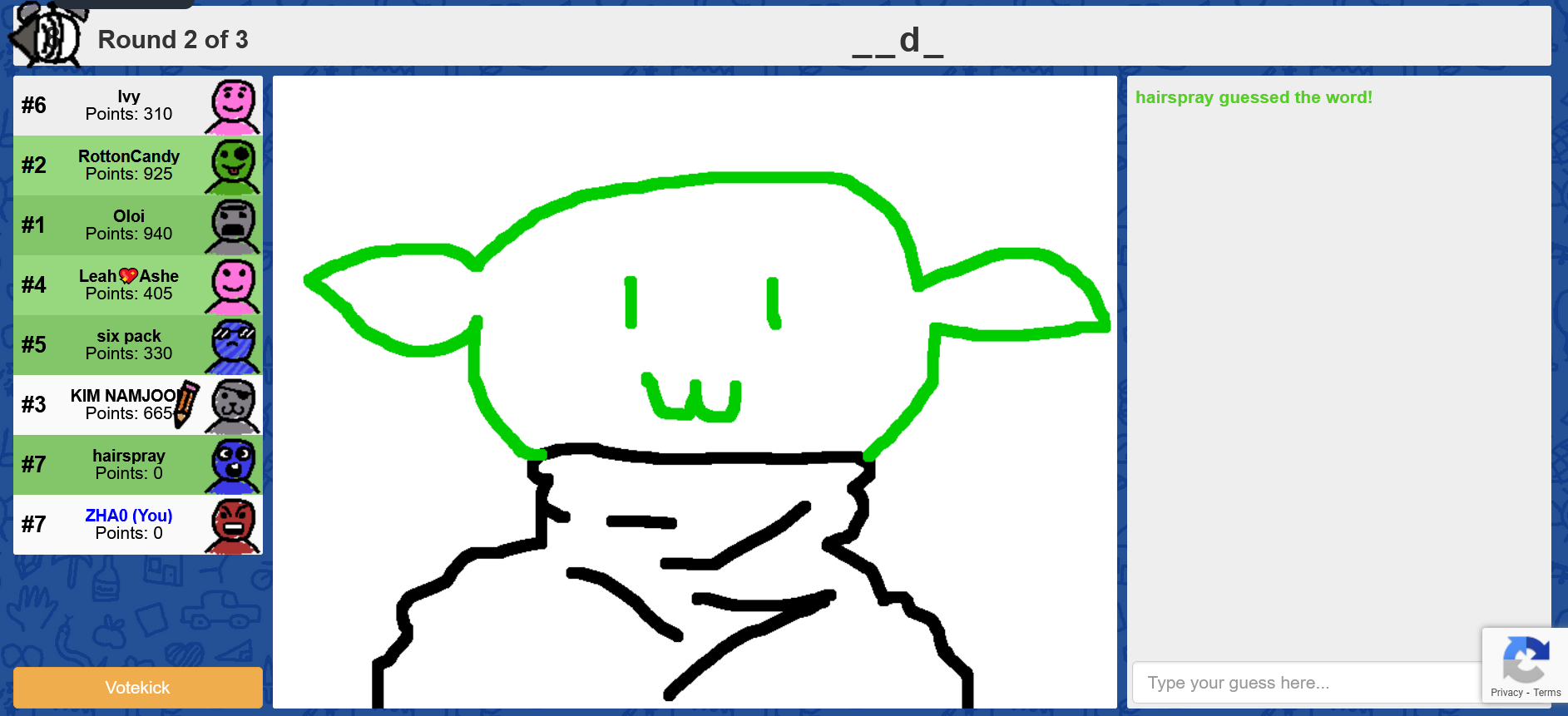

skribbl.io

It’s a popular game similar to Pictionary, except you know how many letters the word is like in Hangman. I found that someone had collected data using a bot that played on the site for months, so I decided to create an exploit for it also.

The idea

The idea is essentially what didn’t end up happening with the Morse code exploit; add possible words into a queue and have a setInterval guess from the queue as fast as possible (without getting banned for spam).

Aside: Looking back, the familiarity with this pattern of fetching data to store for future use probably helped me learn React very quickly. Have you ever written a componentDidMount before?

RegEx

The idea is somewhat simple, but a complicated part is trying to only guess words that fit the number of letters and any letter that is revealed.

|

|---|

| Ackchually he’s called |

For what is revealed here, we want to guess ‘soda,’ ‘Yoda,’ or any four letter words containing a ’d’ in the third spot. This turns out to be a natural place to use regular expressions since they can match patterns in strings.

var hint = $("#currentWord")[0].textContent;

// '__d_'

var regex = '^' + String.raw`\b` + hint.replace(/_/g, '[a-zA-Z0-9]').replace(/ /g, String.raw`\s`) + String.raw`\b` + '$';

// '^\b[a-zA-Z0-9][a-zA-Z0-9]d[a-zA-Z0-9]\b$'

var pattern = new RegExp(regex);

if (pattern.test(word)) { // if the possible guess matches the RegEx

guesses.push(word);

}

The ‘^,’ ‘$,’ and \b symbols are used to anchor the patterns. They only match a string if the pattern begins the string, ends the string, and begin/end the words in the string. For example, this prevents our RegEx from matching ‘scattering’ if we only want ‘cat.’ Any underscore can be replaced by a lowercase/uppercase letter or number.

Automation

The end result makes use of fetch, a valuable tool when interacting with any REST API.

var url = "https://skribbliohints.github.io/words.json";

var guesses = [];

var i = 0;

fetch(url)

.then(res => res.json())

.then((words) => {

setInterval(function() {

if (guesses.length > i) {

$("#inputChat").val(guesses[i]);

$("#formChat").submit();

i++;

}

}, 1500);

for (var word in words) {

var hint = $("#currentWord")[0].textContent;

var regex = '^' + String.raw`\b` + hint.replace(/_/g, '[a-zA-Z0-9]').replace(/ /g, String.raw`\s`) + String.raw`\b` + '$';

var pattern = new RegExp(regex);

if (pattern.test(word)) {

guesses.push(word);

console.log(word);

}

}

})

.catch(err => { throw err });

|

|---|

| Spicy… silverware? |

Conclusion

I ended up learning about code obfuscation, HTML, CSS, the DOM, design patterns, concurrency, higher-order functions, HTTP, JSON, and RegEx all while having fun finding exploits in webgames. Beginners can be discouraged from programming if they never have projects that are small enough to be achievable, fun enough to be motivating, and reward you with something you can actually use. Why don’t we teach programming like this?